Thank You for your interest in The Celestia Project

Celestia: Our Abundant Future

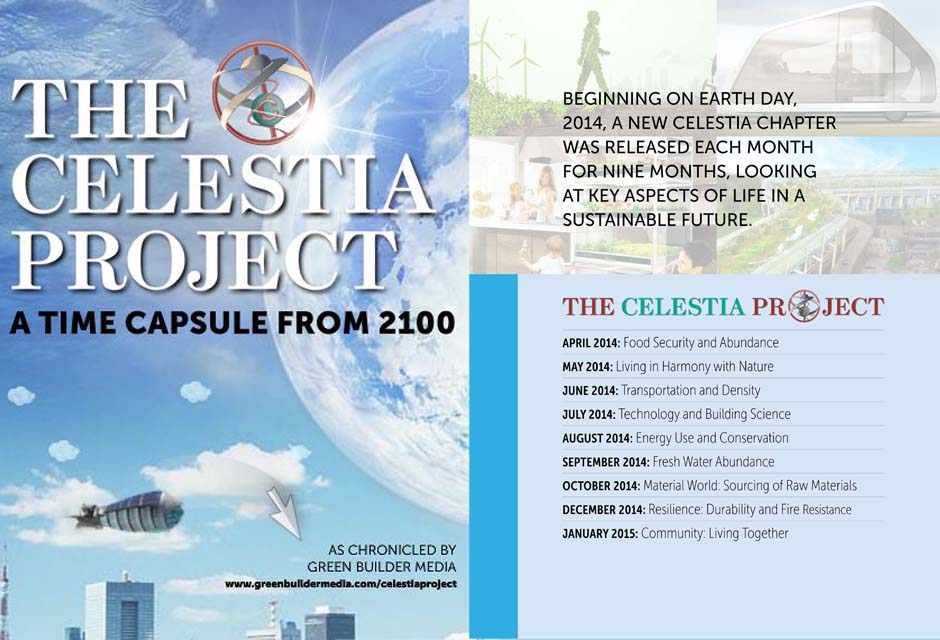

The Celestia Project is a natural step in Green Builder Media's journey. Along with many other endeavors this year, we're working on our second futuristic green home exhibit--more to come on that later. Increasingly, we find ourselves being asked to operate on the leading edge of the green revolution. Our message and our mission need to be clear.

MEETING OF MINDS. At our annual company meetings in February 2014, we set a goal of creating a new framework under which we could organize and present our many projects and publications. New reports on the worsening impacts of Climate Change have made our work seem ever more urgent.

Toward the end of a long session, we set out the plan: We would tell a simple story about life in the future. But Instead of telling the story starting now, why not tell the story backwards? Why not start at a place and time where the major crises of human impacts have been solved, and climate change has stabilized, and show how we got there?

We've spent the last couple of years in close communication with most of the leading voices of the climate change "movement," so we know what we're up against. We know we're out of touch with nature, but solutions exist, such as the trend of people moving back to cities. We know the sharing economy also promises to reduce our ecological footprint, but we're keenly aware that immediate, drastic efforts are needed.

We have many important topics to explore. We believe the Celestia Project offers a way to explore them that is both beautiful and hopeful.

Thank you for joining us on our imagined journey into tomorrow. We truly believe that despite the seemingly insatiable wanting of modern society, a joyful and abundant future lies ahead.—Matt Power, Editor-In-Chief

Winner of an Eddie in the national 2015 Folio competition

More from Green Builder